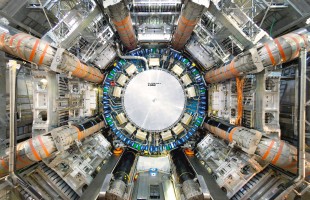

Vier jaar heeft hij protonen met de hoogst bereikbare energie ter wereld op elkaar geschoten, de Large Hadron Collider (LHC) op CERN in Genève, Zwitserland. Maar woensdagochtend om half zeven stonden de metertjes in de controlekamers op nul en was proton physics run II definitief ten einde. Tijd voor een long shutdown, die volgens plan twee jaar zal duren.

In de afgelopen LHC-run is een recordhoeveelheid proton-protonbotsingen vastgelegd in experimenten als Atlas en LHCb, twee detectoren waarin Nikhef een belangrijke bijdrage heeft. Onlangs werd de magische grens van 150 zogeheten inverse femtobarn bereikt, een maat voor het aantal geregistreerde botsingen.

‘We hebben zo ongekend veel data binnengehaald dat we ons de komende twee jaar bij alle analyses echt geen moment hoeven te vervelen’, zegt Atlas-coprogrammaleider prof. Wouter Verkerke van Nikhef. Eerder dit jaar, zegt hij, zag dat er door technische problemen nog niet echt naar uit.

De komende twee jaar, de zogeheten long shutdown, wordt de 27 kilometer lange ondergrondse LHC-versnellerring verbouwd om nog hogere intensiteiten van protonenbundels te kunnen aanleveren. In 2020 moet hij weer in bedrijf komen in de zogeheten high-luminosity run.

De experimenten als Atlas en LHCb, en ook de concurrerende CMS-detector in de ring, gaan dan verder met hun studies van het higgsdeeltje. Ook vervolgen ze hun speurtocht naar onbekende verschijnselen die buiten de gangbare deeltjestheorie vallen, het zogeheten Standaard Model. Tot nog toe heeft de LHC, die energieen tot 13 TeV bereikt, daarvoor geen harde bewijzen aangedragen. Bij de volgende run gaat de energie naar 14 TeV en wordt de bundelintensiteit vertienvoudigd.

Ook de Atlas-detector, gebruikt bij de ontdekking van het higgs-deeltje in 2012, zal de komende jaren verder worden geoptimaliseerd. De LHCb-detector wordt zelfs goeddeels vervangen door een nieuwe opstelling. Onderdelen voor de experimenten worden ondermeer bij Nikhef in Amsterdam ontwikkeld en gebouwd.

De komende weken versnelt de LHC nog bundels lood-kernen, om een oersoep van deeltjes te creëren die in de buurt komt van de materietoestand kort na de oerknal. Het Alice-experiment, ook deels Nikhef, zal die botsingen gaan bestuderen en de vloeistofachtige zogeheten quark-gluonplasma’s die erbij ontstaan. Altijd weer spannend, zegt Alice-groepsleider bij Nikhef prof. Raimond Snellings. ‘Wij hebben altijd maar een paar weken meettijd, dan moet alles goedgaan.’

De Zwitserse Nikhef-promovendus Marko Stamenkovic werkte in de laatste nacht van de proton-run van de LHC in de controlekamer van de Atlas-detector. Hij zag letterlijk de laatste protonen passeren en schreef er de volgende (engelstalige) blogpost over. ‘Met enige vertraging, want tegen 4 uur ’s nachts begint je verstand te haperen.’

Marko Stamenkovic, PhD Student at Nikhef: October 24th, it’s 6:01 and I am sitting in the control room of the ATLAS experiment. The Large Hadron Collider, located at CERN in Geneva, just delivered the very last proton-proton collision of its second run of exploitation. The LHC and ATLAS will keep operating until December, mostly to collect data concerning a different type of physics but this doesn’t concern me directly. Between 2015 and 2018, the ATLAS detector has operated day and night, from April to December, to collect as much data as possible.

It’s in this day and night, but mostly night, that I enter in the story. I am a PhD student at Nikhef and part of my work is to spend 8 hours straight in the control room and make sure that the data acquisition goes without any issues.

When you think about it, a shift in the ATLAS control room is a very weird experience. 8 complete strangers gather 24/7 in a room to watch multiple computers, call other strangers having a phone with them because they have some expertise about a huge machine that other strangers designed and built. Nevertheless, when you have a closer look, you realize that this is the best representation of what a large international collaboration is. Tonight, in the control room, we are 8 physicists, 3 women and 5 men, from 7 different nationalities, as many various academic institutes, collecting the last bits of proton-proton data before 2021. This data will then be distributed to 3000 researchers from 181 institutes located in 38 different countries. The most impressive thing is not only the detector itself but the collaboration as well and all the efforts that people are ready to invest.

Why is this data so important? I was always very curious, from a young age already. What fascinated me the most was matter. What composes me? What is everything made of? Nature tells us in an elegant way that we are mostly made of 3 types of particles: the electron, the up and the down quarks. These 3 different particles have different properties, for example their masses. Physicists often call them the 1st generation.

There exist 2 other generations which are heavier copies of the 1st, the 3rd generation being the heaviest. Our best shot at understanding how these 9 different particles move and interact is a theoretical framework called the Standard Model of particle physics. This theory doesn’t only describe how the various particles interact but also how they acquire mass. It is known as the Brout-Englert-Higgs mechanism and one of its most brilliant prediction is the Higgs boson, a particle that interacts only with massive elementary particles. This is the subject of my PhD thesis.

The predictive power of the Standard Model is extremely impressive. Between 2015 and today, 7 million Higgs bosons were created in the ATLAS detector. I am searching for 3000 of them, produced in a special configuration, that then decayed into a pair of charm quarks (my favorite elementary particle). Most of my time during the upcoming year will be dedicated to finding and understanding these events. Unfortunately, many other particles produced in the collisions are expected to look like a Higgs boson decaying to a pair of charm quarks in the detector. Finding the interesting events will be a difficult task.

Measuring the direct link between the Higgs boson and the charm quark would be a great step in our understanding of Nature. So far, the ATLAS experiment has only measured the direct interaction of the Higgs boson and the 3rd generation. Measuring the Higgs decay to a pair of charm quarks would be one of the first direct measurements of the Higgs interaction with the 2nd generation. If the Standard Model prediction corresponds to the observed data, it would confirm even more that the Higgs mechanism is responsible for the generation of the mass of elementary particles. If we measure a deviation from the prediction, it would be a strong hint that there’s another theory out there, waiting to be found. This theory could maybe even explain why the masses of the elementary particles are so different from each other, currently not answered by the Standard Model.

Of course, there is way more than the Higgs boson in the current particle physics research. The ATLAS collaboration is investing a lot of efforts into testing very precisely the Standard Model predictions but also new theories that could result in a deeper explanation of the universe. At the beginning of my shift in the control room, someone said that today was maybe the day we would find new particles. Maybe in the very last event recorded by the ATLAS detector?

Today, we played a tiny part in the history of the ATLAS experiment. So tiny that I will probably be the only one to remember it but contributing to this big adventure and being part of this is a unique feeling. Whatever we learn from this data, I know that our efforts helped make it possible. This is what it means to be part of a large international collaboration! ~ Marko